Mitchelville Introduction

This March, Mitchelville is in the forefront of the Hilton Head community as the sold-out Lean Ensemble’s production of the play, Mitchelville debuts. On Saturday, March 25, the annual “Blues & BBQ” fundraiser will take place from 3-7 pm. We asked local resident, Rebecca Edwards, to write an introduction to Mitchelville for those who aren’t familiar with the story or what it is.

“It seems to me a better time is coming.” —Union Army Major General Ormsby Mitchel

In September 1862, General Mitchel addressed a congregation of formerly enslaved people officially known as “contraband” at the First African Baptist Church on Hilton Head Island. His speech was equal parts empowering and cautionary.

“What will you do with the black man after liberating him?” began General Mitchel. “We will make him a useful, industrious citizen… This experiment is to give you freedom, position, homes, your families, property, your own soil.”

General Mitchel then went on to warn, “The whole North, all the people in the Free States, are looking at you with great interest… If you fail, what a dreadful responsibility it will be when you come to die to feel that the only great opportunity you had for serving yourselves and your oppressed race was allowed to slip. But if you are successful, this plan will go all through the country.”

Six weeks later, General Mitchel died from yellow fever but the town of Mitchelville began to thrive as the first self-governed freedman’s town in America.

“Stand for something or you will fall for anything. Today’s mighty oak is yesterday’s nut that held its ground.” —Rosa Parks

In order to tell the full story of Mitchelville, however, we need to step farther back in time. November 7, 1861 the Union forces captured the Sea Islands of South Carolina after the five-day Battle of Port Royal and Hilton Head Island (specifically Drayton Plantation) became the headquarters for the Union Army.

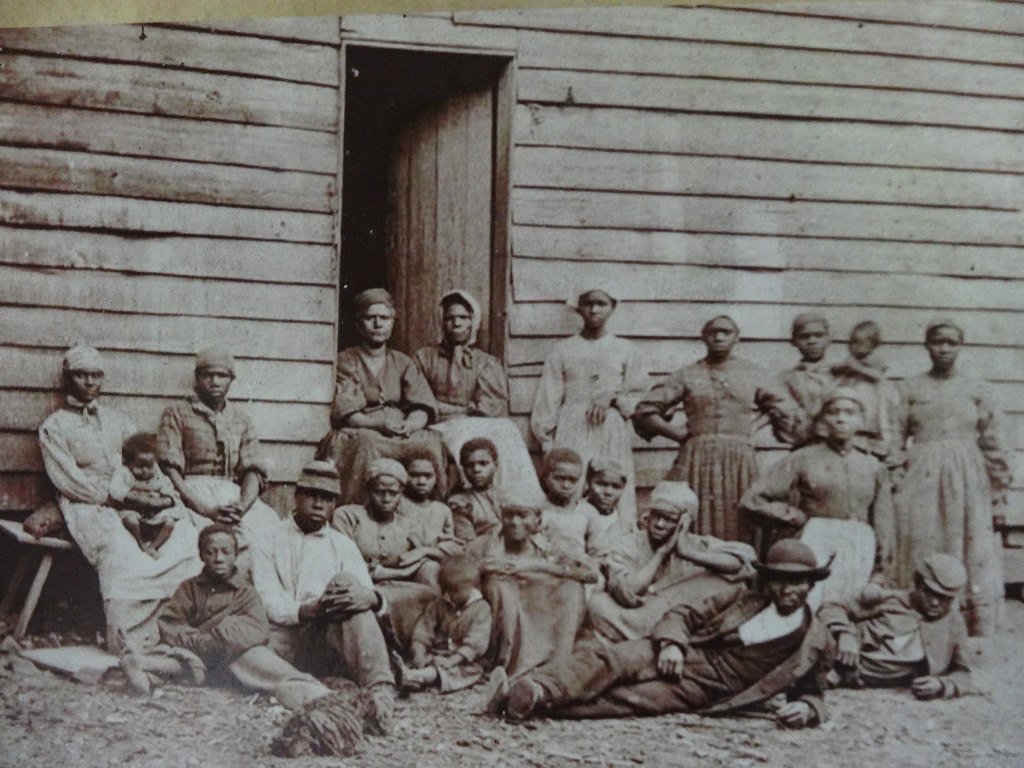

The formerly enslaved arrived to Hilton Head by the hundreds and sought refuge with the Union Army. According to ExploreMitchelville.org, “The new residents began working for pay on base, unloading supply ships, serving as waiters and housekeepers for Union officers, washing clothes, working in the commissary, bake shop, garden, and hospital, while children played nearby. Moreover, since cotton was still the leading export of the United States, it continued to be harvested by the formerly enslaved, but now for a wage.”

“There was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.” —Harriet Tubman

But the transition from slave to freedman was not easy. December 1862, Edward Pierce (who supervised the work of contrabands in Virginia), was sent to Mitchelville. He reported back that the “contraband should have wages, better food, and education. He also reported that the formerly enslaved were in danger of destitution, as food and clothing were becoming scarce.”

In February 1862, Army General David Hunter began enlisting the freedmen in the Union Army with the help of Abraham Murchinson (a former slave from Savannah and who founded the First African Baptist Church on Hilton Head). Ultimately, however, their regiment was disbanded because the US Army did not “fully support this enlistment effort and refused to pay the colored troops.”

By fall, General Mitchel replaced General Hunter, delivered his speech at the First African Baptist Church, and held a contest between Union Army engineers and the freedmen to find the best cabin design. The freedmen won and construction began on the homes situated on quarter acre lots.

“Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom.” —George Washington Carver

From the beginning, education was considered an integral part to the success of Mitchelville. Requiring schooling for every child age six to 15, Mitchelville was the first community to make education mandatory in the state of South Carolina.

“The duty of today is to meet the questions that confront us with intelligence and courage.” —Frederick Douglass

For over a decade, the residents of Mitchelville continued to work tirelessly to fortify their town and hold on to their land, but in April 1875 Drayton Plantation was returned to the heirs of its former owner. ExploreMitchelville.org reports, "The Drayton heirs, however, were not interested in planting the lands and began to sell it off to anyone interested in making purchases, including many freedmen. It was during the last quarter of the nineteenth century that most, if not all, of Mitchelville was purchased by a black man, March Gardner.”

Mitchelville also survived the devastating hurricane of 1893 and decades of land disputes. In 1950 the Hilton Head Company purchased the remaining land and in 1988 Mitchelville was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today much is being said and done to preserve what is left of Mitchelville. Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park’s masterplan includes an 18,000 square foot visitors center, an event lawn, and eight to ten reconstructed houses. The land is sacred. Its soil is rich with history and the words of the people who not only founded Mitchelville but to all the people who spoke up for a “better time”.